HEALTHY TRAVELLING WITH WARFARIN AND AFIB – blog post 14 February 2021

Terracotta Warriors, the Great Wall and Chilli chicken and rice

I have been to China on several occasions and it is somewhere I could go back to again and again. There are so many different, inspirational and easy-to-cook styles of cooking using a huge variety of foods. Northern China has the spicy, pepper-based food I love so much and my blog today is about that area. When I talk about ‘pepper’ in northern China, it is not the traditional black or white pepper of south Asia but, rather, the seed of a prickly ash, which is quite a distinct flavour in itself.

In 2005 I was a travelling scholar for Macquarie University in Sydney. My task that year was to travel through China acquiring a deeper knowledge of the Qin and Han Dynasties which covered the period 221 BCE to 220 CE. This is the period of the famous Terracotta Warriors and the building of the Great Wall of China. I was then to develop teaching resources for high school students, including a website with attached work, on my return. It is still used today.

We based ourselves in Xian near the Drum Temple so that we could walk out to all the places we wanted to see around the old city. We were next door to the Muslim quarter

and often found ourselves watching the stir-frying of foods and learning just how fast street food could be cooked and how everything was prepared beforehand. The great thing was that I could say ‘that, that, not that and that’ and straightaway I had my meal cooked in front of me.

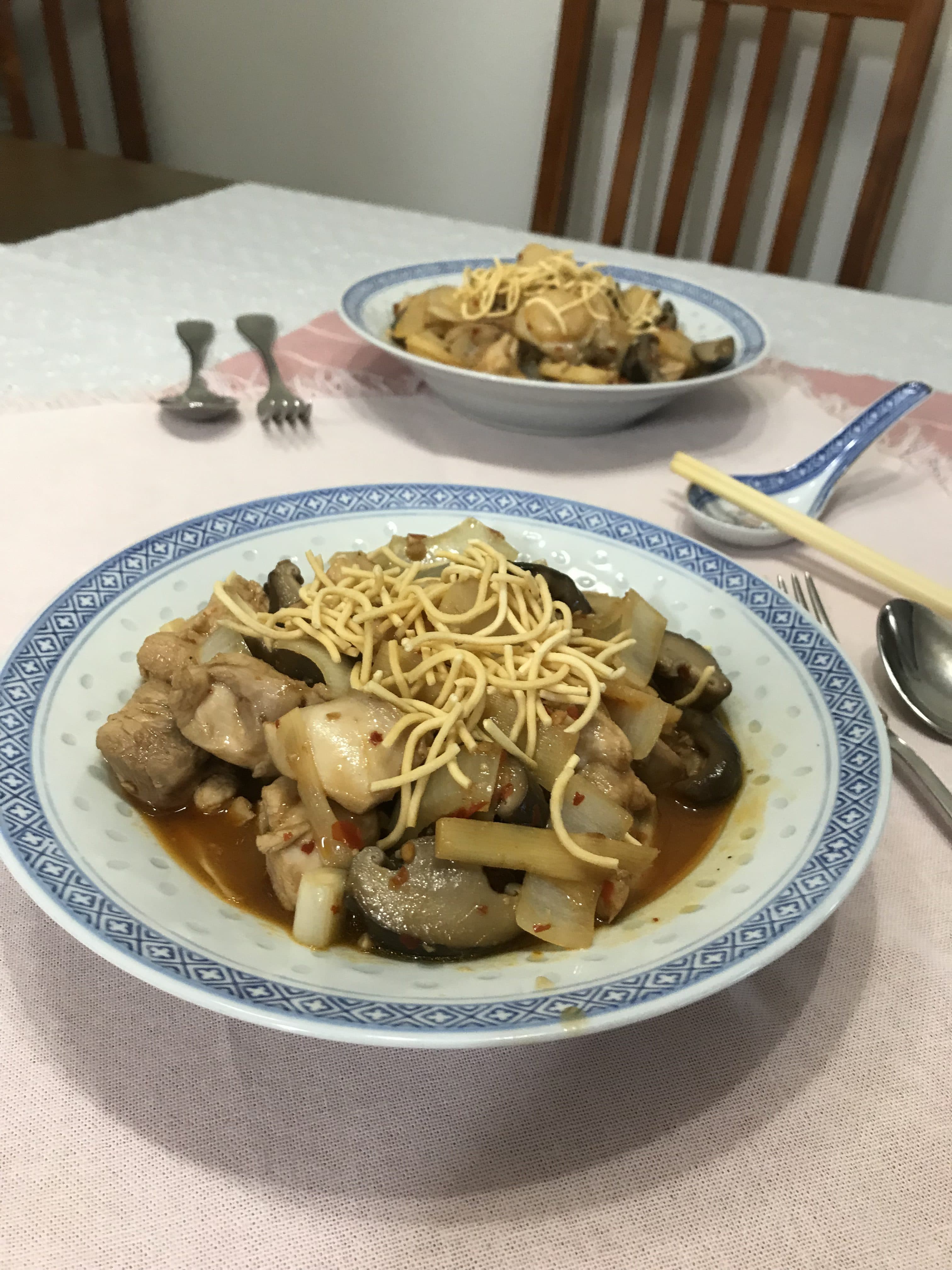

It was here that I learnt that with any stir fry there is a process no matter what you are including and that everything should be cut up and prepared beforehand because the cooking takes so little time. Firstly, after everything is chopped up and ready, you begin by activating the vegetable-based flavours to release their oils such as their local pepper, ginger, garlic and chilli. Secondly, you put into the stir fry all the ingredients from the ones that take the longest cook such as chopped water chestnut, onions (almost always the brown version). Thirdly, add the beaten eggs, fresh field or shitake mushrooms and the softer vegies such as bean sprouts and enoki mushrooms. Fourthly, the finely shredded, sliced or chopped meat is added. Only then do the softer spices such as cumin, dried coriander, turmeric powder and saffron go in just before the liquid, usually fish sauce for salt, soy sauce for salt, tomato sauce for sweetness and, even, a simple beef or chicken stock. Too much cooking can destroy the softer spices and give them a burnt taste. If necessary, a thickener will be added to the sauce.

By this time, my mouth was watering as I stood next to the food stall just waiting to taste the food. At home, it brings everyone to the kitchen. You do not need a wok to cook a stir fry. Just a small frying pan or even a saucepan will suffice as long as it is big enough to stir fry and not stew.

China is one of the easiest places to eat out when travelling with warfarin and afib. This is mainly because what is in the food is, generally, apparent and can simply be avoided. The exception is in some of their rice and pastry wrapped dishes and the occasional hot pot. However, you can ask. As well, the food is usually cooked for you and infront of you. It is almost never held in a bain marie. This is a very safe cooking style for travellers as the heat of the oil destroys any chance of contamination. Also the oil used is likely to be peanut oil although there is a move now to canola and cotton seed oil as they are cheaper. Personally, I prefer peanut and canola oil both of which are safe for warfarin users as the quantity used is minimal. I don’t like the aftertaste of cotton seed oil.

There is also a distinct difference in traditional foods. In the north it is Szechuan or Muslim influenced food the further north and north-west you go. In the south of China and up the coast to Beijing, it is generally based on Cantonese, Hong Kong or Fujian food although, today, all foods are common across the whole country. In the north, which this blog is about, wheat- and millet-based foods such as wheat noodles and wheat pastries, and hot, spicy foods, are traditional as it is in a colder climate. Although rice is available, it is more common in the southern provinces.

‘Bread’ is generally found in the form of steamed buns and steamed dumplings. These may be plain, sugar glazed or filled. All are usually safe because the filling is almost always cook chicken, mushroom and roast pork unless, of course, you don’t eat pork.

Many of the hotpots and steamed dishes of the north have been influenced by the Middle Eastern countries and contain honey, raisins and nuts but also dried apricots and are based on the cheaper cuts of meat such as mutton and goat. Beef is expensive and too important as a beast of burden to eat. They use flour as a thickener rather than okra (Middle Eastern/African foods). Ground rice is also used but that, traditionally, is usually further south.

Increasing amounts of fresh green vegies are being thrown into all sorts of dishes. It is very easy to say ‘no’ if you wish to because the great majority of Chinese under the age of about 40 and over the age of 60 or 70, speak good English. Someone nearby will be able to translate what you are saying or you could show them the following which means ‘I cannot eat green vegetables and fruit due to a medical condition. Please do not place any fresh or cooked greens onto my plate’. The reality is that you can eat them, IF you can control the quantity of fresh greens, which is difficult to do when travelling. I found this a very helpful statement and carried it on my phone. Everyone I have shown such statements to in their own language over the years, has been very helpful. I even had a little girl of 8 help us to translate my request. She had perfect English. I do not speak Cantonese or Mandarin beyond the basic hotel expressions and I am assured that the following is correct. All I can say is that it worked for me.

Simplified – 由于医疗条件,我不能吃绿色蔬菜和水果。请勿将新鲜或煮熟的蔬菜放在盘子上。

Yóuyú yīliáo tiáojiàn, wǒ bùnéng chī lǜsè shūcài hé shuǐguǒ. Qǐng wù jiāng xīnxiān huò zhǔ shú de shūcài fàng zài pánzi shàng.

China is an exciting place to visit. It is as safe as anywhere else in the world with the usual caveats. Away from the coast and into the hinterland, such as Xian and the Terracotta Warriors, and beyond to Taiyuan, Lanzhou, Urumchi and Kashgar, is worth every effort you are prepared to make. I have enjoyed every visit there. You can too.